After having spent 24 hours on the ferry from Egypt we arrive in Wadi Halfa, Sudan. Kids in hands and with all our gear we clear customs (after having waited 30 minutes for the custom officers to  arrive) and board an old shared land rover taxi heading into town. Seats on the wooden benches in the back are sold individually for the bargain price of 20 Sudanese Pounds (SDG) – around 40 US cents.

arrive) and board an old shared land rover taxi heading into town. Seats on the wooden benches in the back are sold individually for the bargain price of 20 Sudanese Pounds (SDG) – around 40 US cents.

Wadi Halfa is a basic town. Nothing to see. Not much to do. We check in to Cleopatra Hotel (pronounced Kilopatra) – a 5-bed room with A/C and outside toilet costs us only 5 USD. BBQ chicken al fresco style in the center of town with bread and drinks for the whole family sets us back another 5 USD.

For a few hours I wait for our required visa registration in an office with some cheerful and super  friendly police officers. After that we buy bus tickets. The bus leaves for Khartoum at 3.30 am and the journey takes 12 hours we are told.

friendly police officers. After that we buy bus tickets. The bus leaves for Khartoum at 3.30 am and the journey takes 12 hours we are told.

The bus is made in China. Modern but worn. Mirrors hanging down like goofy’s ears. The driver is young. Worryingly young. His co-driver doesn’t drive and is only a kid. He is the ticket seller and the passenger collector. We estimate him to be just 16 years old. He acts strange and possibly he has some sort of a mental handicap.

In the bus we soon after fly through the night. Outside it is dark as death. The speedometer maxes out at 140 Kmph and that is where the needle seems forever stuck. The desert outside that we cannot see must be flying past. The driver is crazy. A few times he almost looses the bus on the  winding roads. Every other passenger has peacefully gone straight to sleep. No one minds that we are doing 140+ on narrow roads in Sudan in a bus that obviously has no seatbelts. Inshalla will we get there. If gods wants us to. I try to push a 1.000 SDG note (20 USD) into the drivers hand for him to slow down. He blankly refuses. And says something in half Arabic that probably means that everyone else wants to arrive on time.

winding roads. Every other passenger has peacefully gone straight to sleep. No one minds that we are doing 140+ on narrow roads in Sudan in a bus that obviously has no seatbelts. Inshalla will we get there. If gods wants us to. I try to push a 1.000 SDG note (20 USD) into the drivers hand for him to slow down. He blankly refuses. And says something in half Arabic that probably means that everyone else wants to arrive on time.

‘Shuei shuei’ I tell the driver as the dawn slowly breaks. ‘take it easy’ in Arabic. Sometimes that makes him slow down a little. But as soon as I am back in my seat he speeds up again. We stop for breakfast and lunch in numerous check points and seemingly everywhere along the way to collect new passengers (coordinated via the co-drivers mobile phone). Which means that to arrive on schedule we need to maintain an average speed of at least 150 kmph. The driver and particularly the boy co-driver gets enough of me. They don’t give a shit about ‘shuei shuei’ they just want to get there. So they start making fun of me in front of everyone. There is nothing I can do. Except being laughed at and praying we will all arrive in just one piece.

When we overtake the driver seems indifferent to the oncoming vehicles. He just overtakes. Everyone else has to move. Fortunately, no one wants to collide with our Chinese missile doing close to 200 kmph. Anyone who is unfortunate enough to be in our path will just have to leave the road to give way. For the next hour not much happens. Except of course that the co-driver gets in a fist fight with a passenger who is unwilling to move seats as he is instructed. This obviously causes our heavy drapes – much needed to keep out the fierce desert sun – to fall down. ‘TIA’ I think to myself. This is Africa.

After seven hours on the road the bus breaks down. The benefit is that we are no longer at risk of dying. Unfortunately we are also stuck in a very remote and very hot desert with no aircon since the engine can no longer run and operate it. A row of other busses – all doing the same route at the same time in a convoy – are stopping in at the small rest station where we are parked. Most are full, but I eventually find an old bus with 4 spare seats and arrange how much we should pay for those. I hurry to fetch the rest of the family but before I can get them out of our broken bus the other bus suddenly just leaves and leave us in the desert. We are five hours away from Khartoum. Stuck in the middle of nowhere surrounded by only sand.

The driver of course is also the sole responsible for fixing the bus. In his long white, spotless rope he disassembles the engine. He takes out two rubber belts and two huge motor parts and starts opening them. Soon after there are metal rings and little metal balls all over the floor. He hammers away. It looks like something no one on earth will be able to put back together again.

‘Do you like Sudan’ a fellow passenger who is studying to become an engineer and who speaks a little English asks. We have slept in a basic hotel without proper mattresses, eaten chicken, waited for hours on our registration. We have gotten up in the middle of the night to take a bus in which we have feared for our lives and for that we have been ridiculed. ‘Helua chedit’ I usually answer when I get this question in the Arab world. ‘Very beautiful’. But it doesn’t seem to fit the occasion. ‘La’ I just say – ‘no’ – and look the engineer straight in the eye. That makes him sad.

‘Maybe we have to sleep in the bus’, the engineer says after two fruitless hours of bus repair. Apparently – as I understand him – we need a spare part that needs to arrive with the bus the next day from Khartoum.

At least there is a little cafe so we can get water and tea and biscuits. Twenty minutes later everybody smiles. From deep inside the storage rooms under the bus someone has found the spare part that we need. The infinite number of disassembled motor parts are put together by a few mechanical geniuses and forty minutes later we are rolling again.

We are three hours late and the driver obviously needs to make up for it. So we go even faster. We overtake like madmen and after many hours of maniac driving we almost get used to it. The in-bus video system symptomatically shows a movie with local men who throw chairs at each other. And young girls looking melancholically at an old man with a turban who sings affectionately. In the end they all dance and sing. Then the screen turns to snow. Volume is still at max and the sound system sounds like something from – yes – Sudan. With scrambling noises and snow on the screen the bus-ride from hell continues.

Suddenly it starts raining and the roads turn slippery. Slippery roads and breakneck speeds in one of the driest deserts on the planet. ‘What else can happen on this trip?’ I think to myself.

As we approach Khartoum the number of oncoming vehicles increases. In front of us is a very slow moving truck and for once even our crazy driver can’t overtake. At least that is what we think until he takes the bus of the road and into the sand and try overtaking on the inside! At least he reduces the speed before doing so in order for us to – barely – stay upright. But the reduced speed means that we get trapped in the sand instead. While I am considering if now is the time to go and kick the driver in his balls he narrowly and with fast spinning wheels manages to accelerate away from the soft sand and back on to the tarmac.

When we finally arrive in the western Omdurman district of Khartoum we choose to stay on the bus because someone tells us it will continue to the center. Instead it goes north in the wrong direction, through the slum, twice in circles (according to my GPS – the engineer states that ‘the driver does not have GPS so he just goes the way he knows..) and finally after two hours of hellish capital traffic jam and slums we arrive at another bus station further away from our hotel that the initial one in Omdurman. Welcome to Khartoum.

Around 17 hours after we started our journey the driver shakes my hand and says goodbye. The same driver who drove the whole way, fixed the bus and managed to stay awake even though he started at 3 am. I shake his hand and thank both God and Allah that we made it. Odds are that this driver will not grow old I think to myself as the tail lights of his Chinese missile disappears into the Khartoum night. The bus station is just red earth with scattered litter. In one of the most decrepit taxis I have ever taken (except for in southern Mali and in Niamey, Niger) we finally arrive at our hotel in downtown Khartoum. A few minutes prior to when my 9 year old son Jonas (according to himself) would have been forced to relieve himself in his pants.

Khartoum is at the same time chaotic, desperate, friendly and fun. It has fancy shopping malls and refugees from the war in Syria begging in the streets. Street vendors galore. Gridlocked traffic with beaten up tuk-tuks and rusty, old yellow taxis. Floodings and mud in the central streets due to the lack of draining. Police in various uniforms. Street signs with strange Arabic writing. Number plates with strange Arabic numbers (in the western world we use ‘arabic numbers’ but in Sudan they use the’east-arabic’ numbers with different symbols). Never ending queues at the gas station selling gas at the official rate of 8 SDG (10 US cents). Friendly, smiling, welcoming Sudanese people. And the occasional undercover cop. It may not be for everyone – but we think it is fun.

Until recently photo permits and travel permits for travel outside of Khartoum have been required. I visit the tourist ministry and gets invited to the director’s office. His name is Siddig Gasmelseed – a friendly and well educated man. He informs me that photo and travel permits are no longer needed as per a recent presidential decree. He even gives me a copy of this decree that soon will come in handy..

‘Taking photos in Khartoum is asking for trouble’ my very old (and very thin) Lonely Planet guidebook chapter to Sudan states. I am not sure why and having obtained my ‘presidential permission’ I choose to ignore that advice.

Mostly I have no problems – especially at tourist sites – but when video recording a chaotic traffic intersection a guy tries to take my iPhone from me. I narrowly manage to hold on, quickly deletes the video and he goes away. At another time an undercover police officer (at least that what he says he is) goes bananas when I take a portrait of an old man (who is very eager to have his portrait taken) in front of our hotel. My presidential decree and the hotel staff and their friends who have previously earned a small commission helping me black market money change help me – so I ‘escape’ without paying.

To get Sudanese pounds we exchange dollars at the black market – mostly near the main Souq. In July 2018 the rate is close to 50 SDG for a USD. The inflation is through the roof and the country is close to collapsing economically. When South Sudan gained independence in 2011 they took with them around 3/4 of the oil resources of the former unified Sudan. For us this means that our pockets are constantly flowing over with huge wads of cash – the largest note 50SDG being worth only about a dollar.

‘Police’ a man close behind me suddenly shouts just after I have exchanged a 100 USD on the black market in the street. ‘Fuck’ I think fearing that I will now be dragged to the nearest police station. Soon after however the man shows me a pair of fake sunglasses with ‘Police’ written on one of the glasses. Like most of his fellow citizens he is a kind and welcoming man. I smile to myself when I walk away.

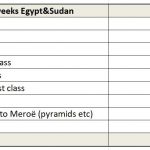

Through Ahmed in Raidan Travel (highly recommended, raidantravel@gmail.com) we go on a 150Euro 2 days/1 night tour to the pyramids of Meroë and the temple ruins of Naga and Musawwarat. The driver is Hadi (‘the quiet one’ in Arabic) a retired criminal cases police officers  who at a nice and easy pace takes us through the country side the approximately 200 km to the pyramids.

who at a nice and easy pace takes us through the country side the approximately 200 km to the pyramids.

Less than three weeks ago we were in a sea of tourists in front of the pyramids of Giza in Egypt.  This late afternoon we are now watching the Nubian Pyramids at Meroë in Sudan. There is no other tourists. A few camel drivers come rushing in (after their souvenir selling friends on the gate have called upon them). Apart from that we have the more than 200 pyramids in the fairy tale desert dune landscape all to ourselves. An hour on a camel costs only 2USD and we feel like Lawrence of Arabia for a while and our kids are happy desert campers. For 60 USD we get a room at the not yet opened Radian Tourist Village close by which makes a morning revisit to the pyramids possible. Again we have the whole complex to ourselves except for some working men who for reasons unknown are shifting sand by wheelbarrows.

This late afternoon we are now watching the Nubian Pyramids at Meroë in Sudan. There is no other tourists. A few camel drivers come rushing in (after their souvenir selling friends on the gate have called upon them). Apart from that we have the more than 200 pyramids in the fairy tale desert dune landscape all to ourselves. An hour on a camel costs only 2USD and we feel like Lawrence of Arabia for a while and our kids are happy desert campers. For 60 USD we get a room at the not yet opened Radian Tourist Village close by which makes a morning revisit to the pyramids possible. Again we have the whole complex to ourselves except for some working men who for reasons unknown are shifting sand by wheelbarrows.

In total we spend a week in Khartoum. Unfortunately the two top things on my list to see and do are taking place at the exact same time – Friday after the prayer. Nubian wrestling at the stadium  and traditional dancing at the ‘Hamad el Neel’ Muslim cemetery. Hoping for light traffic on the day of prayer we take the chance and try to see both. We hire kind Ali and his narrow, little blue minibus to take us to both (4 hours including petrol for just 10USD). The wrestling starts at 4 pm and the Muslim dance ends at sunset at around 6.30 pm.

and traditional dancing at the ‘Hamad el Neel’ Muslim cemetery. Hoping for light traffic on the day of prayer we take the chance and try to see both. We hire kind Ali and his narrow, little blue minibus to take us to both (4 hours including petrol for just 10USD). The wrestling starts at 4 pm and the Muslim dance ends at sunset at around 6.30 pm.

The wrestling stadium of course turns out to be in Souq Sita much further away from the cemetery than expected (and not where listed in Lonely Planet). There is no other children at the stadium and Charlotte counts only three other women.  We seat ourselves with the general public – lots of friendly men in white ropes and the accompanying round ‘kufi’ hat. Unceasingly we are offered fruit and nuts. Soon after we are invited to sit in the VIP sections but we turn the kind offer down since we quite enjoy being among the friendly common people. The stadium is set at a backdrop of surrounding slum and offers great photo opportunities with people sitting everywhere on the walls. The wrestling starts 20 minutes after 4pm which allows us for only 25 minutes of watching.

We seat ourselves with the general public – lots of friendly men in white ropes and the accompanying round ‘kufi’ hat. Unceasingly we are offered fruit and nuts. Soon after we are invited to sit in the VIP sections but we turn the kind offer down since we quite enjoy being among the friendly common people. The stadium is set at a backdrop of surrounding slum and offers great photo opportunities with people sitting everywhere on the walls. The wrestling starts 20 minutes after 4pm which allows us for only 25 minutes of watching.

Google maps says 45 minutes to the Muslim cemetery but the first 100 meters to the junction alone takes half an hour due to insanely clustered traffic (this is where I video recorded the traffic jam and almost lost my iPhone).

From the intersection Ali luckily takes us through back roads with little traffic. The reason for the limited traffic being that the gravel roads are flooded and have giant holes that we are just barely  able to pass through. At exactly 6 pm – half an hour before the sun sets we arrive at Hamad El Neel. People here are kind, welcoming and curious and instantly allow us and our blond children to go to the inner circle of the main dancing. As the sun sets the scene is a photographers paradise and I happily snap away while the locals are taking at least the same amount of pictures of our children.

able to pass through. At exactly 6 pm – half an hour before the sun sets we arrive at Hamad El Neel. People here are kind, welcoming and curious and instantly allow us and our blond children to go to the inner circle of the main dancing. As the sun sets the scene is a photographers paradise and I happily snap away while the locals are taking at least the same amount of pictures of our children.

The next day we have hired Ali again (100 km, 5 hours, 15 USD) to take us to the camel market. Unfortunately we are taken to another cattle market with just a few camels instead. The benefit being than when returning to the main camel market (Mowailih I think it is called even though some locals also said ‘Al Myhra’) we pass ‘Souq Libya’ and experience one of the poorest, dirtiest, crowded and traffic congested markets I have seen worldwide. And we get to go on flooded back roads where people are sleeping on beds right in the streets when we take the short cut to the giant camel market.

A man in a pink shirt and a man in white ropes run around trying to make the big horned cows run  in the same direction as we approach the giant market. Nubian men in front of Toyota pickup trucks are counting money in front of camel herds. Boys ride around on donkey carts carrying rusty barrels. And a truck with a crane is dispensing the camels that have been sold to other trucks.

in the same direction as we approach the giant market. Nubian men in front of Toyota pickup trucks are counting money in front of camel herds. Boys ride around on donkey carts carrying rusty barrels. And a truck with a crane is dispensing the camels that have been sold to other trucks.

That is how our ten days journey around Sudan ends. Sudan may sound hardly accessible, troublesome, tough, poor and a little dangerous. It may be no walk in the park but mainly it is a country with one of the most welcoming and hospitable people that we have ever been to. And the attractions – the pyramids, the Nubian wrestlers, the ceremony at the cemetery and the great camel market – are distinct, special and adventurous like few other places on earth.

(sorry for my far from terrific English – I mainly write in Danish and this is just a quick translation for the English speakers)

Great family outing! With one exception, the bus the crazy speeding long bus ride I’d repeat your amazing trip!

Hehe thaksn – and yep you should Leila – amazing country – amazing people – amazing sights that you have all to yourself